In 1978, the initial GPS satellite was launched and named Navstar 1. This marked the start of a vast constellation of satellites that largely dictate our movements and sometimes even impact how we live. The notion of navigation satellites is crucial to modern society, so much so that it’s given rise to a term: Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS), which includes multiple constellations.

The most famous one is the one called Global Positioning System. GPS for short, it’s also the most used, hence the globally-adopted name of the technology. The system consists only of 31 satellites and is run by the U.S. Space Force. There’s also Galileo, a system with 24 satellites in Europe. And, of course, there’s Russia and China, each with its own constellations, Glonass and BeiDou, respectively.

As humans, GNSS hardware serves one purpose: to provide us with guidance and positioning, whether for benign purposes like vacations or more aggressive ones like finding the right target to destroy. Did you know GNSS is also used by spacecraft?

ASA and other organizations have been exploring the possibility of using GNSS signals beyond near-Earth spacecraft operations. In fact, just a few decades ago, they developed methods for spacecraft located up to 22,000 miles away from Earth’s surface to utilize GNSS signals effectively. Now, the question is whether we can apply this technology for navigation on the Moon which is approximately 240,000 miles away. Surprisingly, NASA and other groups are researching this idea as a potential reality rather than dismissing it outright.

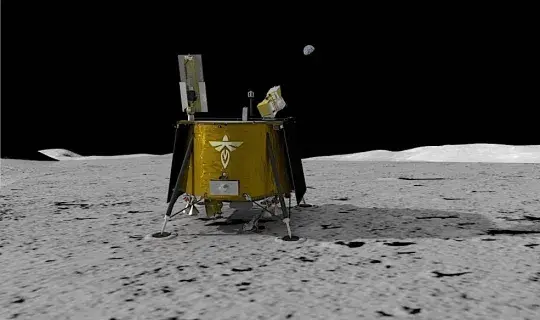

In the year 2024, a spacecraft named Blue Ghost is set to take off on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket and head for the moon. As it travels, it will carry ten different technology demonstrations and science experiments onboard. One of these investigations is known as LuGRE, which stands for Lunar GNSS Receiver Experiment. This project was created jointly by NASA and the Italian Space Agency, with LuGRE itself being made up of several components including a weak-signal GNSS receiver, a high-gain L-band patch antenna, a low-noise amplifier, and an RF filter.

The device’s purpose is to go down in history as the tool that enabled the receipt of a GNSS signal on the Moon’s surface, and it will achieve this by receiving signals from American GPS and European Galileo satellites. This process will begin while still traveling to the Moon, but once it lands in Mare Crisium, LuGRE’s antenna will unfurl, initiating a 12-day-long research project that may last longer.

Besides receiving GNSS signals, the technology will be used to test “lunar navigation capability.” That is, for the first time ever, it will receive GNSS location fixes not only on the way to the Moon, but also on the Moon itself.

It’s important to note that the Magnetospheric Multiscale Mission (MMS) probe achieved impressive feats in signal coverage. In 2016, it utilized Earth satellite signals to determine its position from a distance of 43,500 miles (70,000 km). Remarkably, three years later, the same probe surpassed this achievement by receiving a GNSS signal while situated over twice that distance at 116,300 miles (187,000 km), which is almost halfway to the Moon. Therefore, if you harbor concerns about whether GNSS signals can traverse such vast distances as those involved in lunar missions – let these triumphs serve as evidence they can.

Our most important space exploration undertaking now is the development of a lunar communications and navigation system, aside from the upcoming lunar missions themselves. As long as such a system isn’t in place, we won’t be able to explore and colonize the Moon (and eventually Mars) in the manner we intend. LuGRE departs in 2024, so we won’t be able to find out how fast we can expand to other worlds for about a year.