A QAnon sign at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. Many of the rioters who attacked the Capitol later told investigators they were motivated in part by the online conspiracy theory.

Win McNamee/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Win McNamee/Getty Images

After a mob of pro-Trump protesters breached the U.S. Capitol through a broken window on Jan. 6, 2021, a lone Capitol Police officer, Eugene Goodman, diverted the group away from the Senate chamber. The pack of protesters then chased Goodman up a staircase.

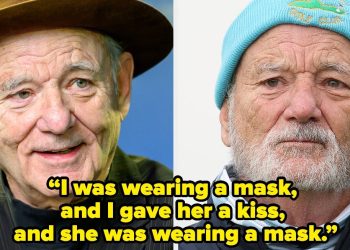

The man leading the mob was wearing a black T-shirt emblazoned with an eagle inside of a large red, white, and blue “Q.”

Douglas Jensen later told the FBI he read content about the QAnon conspiracy theory online daily. He said he had worn the shirt and put himself at the front because he “wanted Q to get the attention.”

Douglas Jensen and other rioters speaking to U.S. Capitol Police in the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. Jensen later told the FBI he had worn the QAnon shirt and put himself at the front of the crowd because he “wanted Q to get the attention.”

SAUL LOEB/AFP via Getty Images/AFP

hide caption

toggle caption

SAUL LOEB/AFP via Getty Images/AFP

Most of the rioters who stormed the Capitol that day were inspired by then-President Donald Trump’s calls to be there. But many, like Jensen, also cited the baseless QAnon conspiracy theory. Over the past four years, the online extremist community has continued to be subtly courted by Trump and some of his most powerful allies.

The theory, which emerged in 2017, claims that Trump is involved in a secret battle against evil members of the alleged deep state, or in other tellings, a powerful cabal of government and Hollywood elites engaged in satanic child abuse. Some QAnon claims and themes echo longstanding antisemitic tropes. An anonymous source called Q, who supposedly had access to high level intelligence, posted cryptic clues, known as Q drops, on online message boards.

“The QAnon community believes that by decoding these drops, one can understand not just the moves and countermoves in the secret battle, but also essentially predict the future,” said Logan Strain, who began reporting on QAnon six years ago after he noticed the movement was not just “staying in the dark corners of the internet.” He co-hosts the QAA podcast under the pseudonym Travis View.

On Jan. 6, many QAnon followers at the Capitol believed they were participating in what is called “The Storm” in QAnon lore. It is supposed to be an apocalyptic-type reckoning when the evil forces are finally punished.

Instead, more than a thousand people have so far been criminally sentenced for participating in the Capitol riot on Jan. 6. More than 1,560 people have been charged with federal crimes.

A changing landscape online

In the aftermath of Jan. 6, a number of social media platforms doubled down on their efforts to ban QAnon content.

By that point, there was a rich online ecosystem of QAnon influencers who had figured out how to monetize spreading QAnon-related content and analysis. In response to the crackdown, influencers moved to less moderated platforms, like Telegram and Rumble.

“The movement didn’t go away by any means. It was just essentially moved and splintered into various networks,” said Katherine Keneally, the director of threat analysis and prevention for the nonprofit Institute for Strategic Dialogue, which studies extremism.

Some QAnon influencers were even recruited to join Trump’s social media platform, Truth Social, by Kash Patel, who’s now Trump’s pick to lead the FBI. Patel previously served as a board member and adviser for the social media platform.

A woman holds a sign referencing the QAnon conspiracy on Nov. 7, 2020, in St. Paul, Minn. QAnon emerged online in 2017 and claims that Trump is involved in a secret battle against evil members of the alleged deep state, or in other tellings, a powerful cabal of government and Hollywood elites engaged in satanic child abuse.

Stephen Maturen/Getty Images/Getty Images North America

hide caption

toggle caption

Stephen Maturen/Getty Images/Getty Images North America

“We also need everybody on Truth Social because it is the only place where we can actually have a conversation without getting shut down by the clown show that is the censorship operation at Titter [sic] and Fakebook,” Patel said in 2022, using disparaging names for Twitter and Facebook during an appearance on the MG Show, which has promoted QAnon.

That same year, billionaire Elon Musk, who’s now one of Trump’s closest allies, bought Twitter and renamed it X. He allowed banned QAnon accounts to return.

Both Trump and Musk have repeatedly shared QAnon-related content on their respective social media platforms, which seems to be a way to wink at the movement.

“It’s incredibly dangerous when we do see high profile figures amplify this language and symbols because it provides adherents this perceived legitimacy to their beliefs and their movement,” said Keneally, who pointed out that QAnon has been associated with violence, including the Capitol riot.

Trump’s brand of politics expanded the Republican coalition to include constituents who believe in conspiracy theories and hadn’t previously been reliable voters, said Joseph Uscinski, a political scientist at the University of Miami. That gave Republican politicians a strong reason to court these newly energized voters. “And that involves saying things that are prominent in QAnon, but saying all sorts of other conspiracy theories, too,” Uscinski said.

Celebrating Trump’s return

QAnon adherents are now celebrating the incoming Trump administration and his cabinet picks.

A 2018 Q drop previously mentioned Patel as “a name to remember.” That history, along with Patel’s rhetoric about the deep state and previous overtures to QAnon — which include signing copies of one of his children’s books with a slogan associated with QAnon (he said he learned the slogan in a movie) and promoting an account called “Q” on Truth Social — have made Trump’s pick to lead the FBI popular among QAnon followers.

When asked about Patel’s past comments about QAnon and appearances on related podcasts, Trump transition team spokesperson Alex Pfeiffer told NPR, “This is a pathetic attempt at guilt by association.”

Strain, the QAA podcast host, said the fantasy among some of Trump’s most ardent supporters for retribution for Trump’s perceived enemies, “very much echoes a lot of QAnon fantasies about a storm of mass arrests.”

Red Pill News, an online show and podcast which shares QAnon content, included in a recent episode a fake alert meant to sound like an official notification from the Emergency Alert System.

“Donald Trump is now your president,” a monotone voice reads after a series of tones. “All deep state traitors are to report immediately to Guantanamo Bay detention camp for court martial via televised military tribunal.”

It’s hard to know how widespread belief in QAnon is today or ever was.

A man wearing a QAnon t-shirt walks through the crowd at a Trump rally on Sept. 25, 2021 in Perry, Ga. The nonprofit PRRI, which conducts polls on religion, found that 19% of Americans believe in the core theories associated with QAnon, up from 14% in 2021. The poll found the number rose to 32% among Republicans who support Trump.

Sean Rayford/Getty Images/Getty Images North America

hide caption

toggle caption

Sean Rayford/Getty Images/Getty Images North America

One challenge is that QAnon is hard to define. Various conspiracy theories that had been floating around the fringes of American culture for decades became incorporated into the movement. “Everything has sort of been sucked into QAnon at one point or another,” said Adam Enders, an associate professor of political science at the University of Louisville who studies belief in conspiracy theories.

As a result, the movement was like a “choose your own adventure book,” said Uscinski.

The nonprofit PRRI, which conducts polls on religion, found that 19% of Americans believe in the core theories associated with QAnon, up from 14% in 2021. The poll found the number rose to 32% among Republicans who support Trump.

Mike Rothschild, the author of “The Storm is Upon Us: How QAnon Became a Movement, Cult and Conspiracy of Everything,” said the QAnon movement showed there was a market for “instantaneous conspiracy content creators” who churn out fresh conspiratorial content on social media pegged to the news of the day.

Influencers learned they could “make money by getting shares and replies and responses and retweets to this outlandish stuff that they put out,” Rothschild said.

There haven’t been new Q drops in years and there appears to be less interest in online content analyzing those drops in the way there once was, said Rothschild.

But ideas QAnon helped popularize, like the idea of a battle against an evil deep state, and anti-vaccine conspiracy theories, have become common ideas on the right.

“QAnon as a movement based around secret codes and clues and riddles doesn’t so much exist anymore,” Rothschild said. “But it doesn’t need to exist anymore because its tenets have become such a major part of mainstream conservatism and such a big part of the base of people that reelected Donald Trump.”